生活与监狱

原标题:Life and Prison

作者:Catherine Malabou

发表时间:2020/10

翻译:小饰

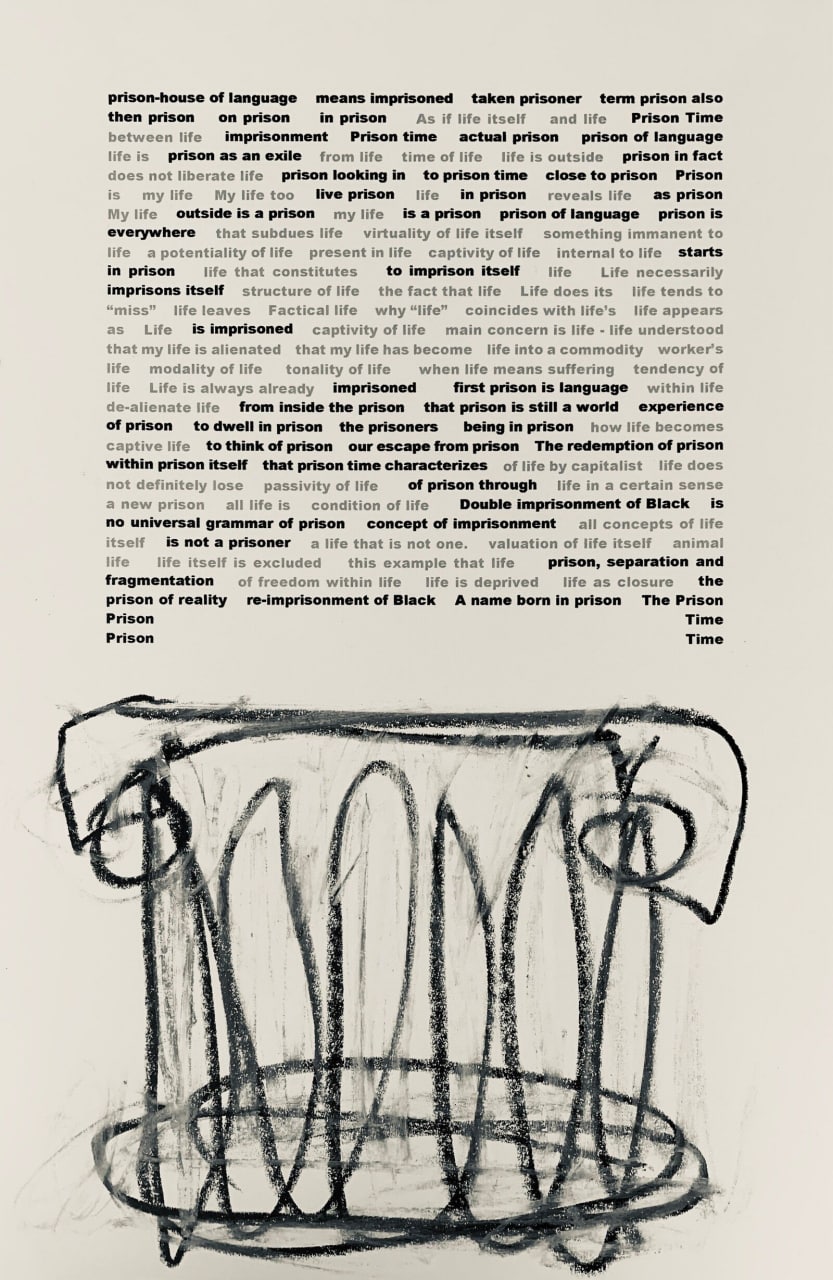

Drawing by Smiljan Radic.

Drawing by Smiljan Radic.

Confinement

The Prison of Language

语言的牢笼

In his inaugural lecture for the opening of the Chair of Semiology at the Collège de France in Paris (1977), Roland Barthes made a very strange and striking statement: “Language is fascist.” His explanation:

罗兰巴特在巴黎法兰西学院神学教席的开幕式做就职演讲时,他作出了一个奇怪和惊人的论述:“语言就是法西斯。”他解释道:

Language is legislation, speech is its code. We do not see the power which is in speech because we forget that all speech is a classification, and that all classifications are oppressive… Jakobson has shown that a speech-system is defined less by what it permits us to say than by what it compels us to say. In French (I shall take obvious examples) I am obliged to posit myself first as subject before stating the action which will henceforth be no more than my attribute: what I do is merely the consequence and consecution of what I am. In the same way, I must always choose between masculine and feminine, for the neuter and the dual are forbidden me… Thus, by its very structure my language implies an inevitable relation of alienation. To speak, and, with even greater reason, to utter a discourse is not, as is too often repeated, to communicate; it is to subjugate: the whole language is a generalized rection… Language—the performance of a language system—is neither reactionary nor progressive; it is quite simply fascist; for fascism does not prevent speech, it compels speech.1

语言是立法,言论是它的准则。我们看不到言语中的力量,因为我们忘记了所有的言语都是一种分类,而所有的分类都是压迫性的......雅各布森表明,一个言语系统与其说是由它允许我们说什么来定义,不如说是由它强迫我们说什么来定义。在法语中(我将举出明显的例子),我必须首先把自己定位为主体,然后再陈述行动,而行动将不再是我的属性:我所做的只是我是什么的结果和结果。同样,我必须始终在阳性和阴性之间做出选择,因为中性和双重性是禁止我的......因此,就其结构本身而言,我的语言意味着一种不可避免的疏离关系。说话,其实更多是构建一种话语,并不是像人们经常重复的那样,为了沟通;而是为了征服:整个语言是一种普遍化的反应......语言--一个语言系统的表现--既不是反动的也不是进步的;它只是法西斯主义;因为法西斯主义并不阻止说话,它强迫说话。

The problem, of course, is that there is no way to escape language; there is no way out. “Unfortunately, human language has no exterior: there is no exit.”2 We are then in the prison-house of language, as Jameson says.3

而问题所在,是无法逃离语言:根本无处可走。“不幸的是,人类语言没有外部:没有出口。”正如詹姆森所说,我们都在语言的牢笼中。

The Prison of Philosophical Concepts

哲学概念的牢房

The capture of language is even more conspicuous when it comes to philosophical concepts. Let’s look at the etymology of the word “concept,” at least in French and in English. It comes from concipere, which itself comes from capere cum, to grasp together. The term concept, then, has the same origin as capture, captivity:

当涉及到哲学概念时,对语言的捕捉就更明显了,让我们看看“概念”这个词的词源,至少在法语和英语中是这样。它来自concipere,而concipere本身又来自capere cum,即一起抓取。那么,“概念”这个词与捕捉、囚禁有相同的起源。

Advertisement

Sound

captive (adj.): late 14c., “made prisoner, enslaved,” from Latin captivus “caught, taken prisoner,” from captus, past participle of capere "to take, hold, seize" (from PIE root *kap- “to grasp”).

captive (n.): "one who is taken and kept in confinement; one who is completely in the power of another," c. 1400, from noun use of Latin captivus. An Old English noun was hæftling, from hæft "taken, seized," which is from the same root.4

The term “prison” also derives from the act of seizing, prendre in French, from the Latin pre(n)siōnem, accusative of pre(n)siō, contraction of *prehensiō, “the action of apprehending the body,” becomes preison, then prison, with the core inflation of pris, past participle of prendre, “to take.”5** In German, the verb greifen (to capture someone) can be heard in Begriff (concept). It seems that philosophy is doomed to redouble the fascism of language.

监狱 "一词也来自于抓捕的行为,在法语中是prendre,来自拉丁文pre(n)siōnem,是*pre(n)siō的指称语,是prehensiō的缩略语,"抓捕身体的行为",变成preison,然后是监狱,其核心是pris的膨胀,prendre的过去分词,"拿"。 5在德语中,可以听到动词greifen(抓人)的Begriff(概念)。看来,哲学注定要使语言的法西斯主义加倍。

I want to link these preliminary remarks with the fact that the most important and profound contemporary philosophical texts devoted to the issue of life practically always comprise, in their very core, a reflection on the prison, on what it is to live in prison. As if life was the privileged victim of philosophical concepts as well as the privileged victim of language, of language’s fascism. Some of the important texts providing us with a reflection on concept, language, captivity, and life include: Captivity Notebooks by Emmanuel Levinas, Marx by Michel Henry, Discipline and Punish by Michel Foucault, Homo Sacer by Giorgio Agamben.

我想把这些初步的评论与以下事实联系起来:致力于生命问题的最重要和最深刻的当代哲学文本实际上总是包括对监狱的反思对生活在监狱中是什么的反思。仿佛生命是哲学概念的特权受害者,也是语言、语言法西斯主义的特权受害者。一些为我们提供了对概念、语言、囚禁和生命的反思的重要文本包括。 埃马纽埃尔-列维纳斯的《囚禁笔记》,米歇尔-亨利的《马克思》,米歇尔-福柯的《规训与惩罚》,乔治-阿甘本的《人的安全》。

I will start by referring to Michel Hardt’s article “Prison Time,” devoted to Jean Genet, to expose first how philosophers generally account for the relationship between life and imprisonment, and second how they explore the possibility of a way out from within language. I will then question the way in which the traditional philosophical approaches to both language and captivity have been challenged by Black thinkers like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Frank Wilderson.

我将首先参考米歇尔-哈特(Michel Hardt)专门为让-热内(Jean Genet)撰写的《囚禁时间》一文,首先揭露哲学家们一般如何解释生命与囚禁之间的关系,其次他们如何从语言内部探索出一条出路的可能性。然后,我将质疑传统的语言和囚禁的哲学方法如何受到黑人思想家如马丁-路德-金和弗兰克-威尔德森的挑战。

Prison and Writing

囚禁与书写

In his article “Prison Time,” Michael Hardt develops a metaphorical connection between actual prison and the prison of language.6 Through Genet’s life, he is able to situate the fact of being in jail in parallel with being trapped within language. Hardt writes: “Inmates live prison as an exile from life, or, rather, from the time of living.” They think: “The first thing I’ll do when I get out is…Then I’ll really be living.”7

在他的文章《监狱时间》中,迈克尔-哈特在实际的监狱和语言的监狱之间发展了一种隐喻性的联系。6通过热内的生活,他能够将在监狱中的事实与被困在语言中的事实平行地定位。哈特写道:"囚犯们在监狱中生活,是对生活的放逐,或者说,对生活的时间的放逐"。他们认为:"我出狱后要做的第一件事就是......然后我就真的活了。"7

Captivity produces the fantasy of an outside: authentic life is outside. Outside walls, and—we might add—outside concepts, outside language. But this fantasy disappears, as Hardt shows, when one discovers that there is no outside, that the outside of prison does not liberate life from its capture:

囚禁产生了对外部的幻想:真实的生活在外面。在墙外,以及——我们或许可以补充,在概念、语言之外。但这种幻想消失了,正如哈特所表明的,当一个人发现外面并不存在,监狱的外部并不能将被捕的生命解放出来时:

Those who are free, outside of prison looking in, might imagine their own freedom defined and reinforced in opposition to prison time. When you get close to prison, however, you realize that it is not really a site of exclusion, separate from society, but rather a focal point, the sight of the highest concentration of a logic of power that is generally diffused throughout the world. Prison is our society in its most realized form. That is why, when you come into contact with the existential question and ontological preoccupations of inmates, you cannot but doubt the quality of your own existence. If I am living that elsewhere of full being that inmates dream of, is my time really so full? Is my life really not wasted? My life too is structured through disciplinary regimes, my days move on with a mechanical repetitiveness—work, commute, tv, sleep… I live prison time in our free society, exiled from living.8 那些自由的人,从监狱外面看着里面,可能会想象那些自由的人,在监狱外面看着里面,可能会想象他们自己的自由是在与监狱时间的对立中被定义和加强的。然而,当你接近监狱时,你会意识到它并不是一个真正的与世隔绝的、排外的场所,而是一个焦点,是一个权力逻辑的最高集中地,而这个权力逻辑通常分散在世界各地。监狱是我们社会最现实的形式。这就是为什么,当你接触到囚犯的存在问题和本体论的关注时,你不能不怀疑你自己存在的价值。如果我在其他地方过着囚犯们梦寐以求的完整存在,我的时间真的如此充实吗?我的生命真的没有被浪费吗?我的生活也是通过纪律制度来安排的,我的日子在机械地重复着--工作、通勤、看电视、睡觉......我在我们的自由社会里过着监狱生活,在生活中流亡。

In a certain sense, life in prison just reveals life as prison. My life outside is a prison, my life as a free subject is a prison. Because I speak. Because I am a speaking subject. Being a speaking subject in the prison of language paradoxically brings me close to those who don’t speak, to animals, animals in captivity, when they develop what is called stereotypic behaviors, made of repetition and routine.9

在某种意义上,在监狱里的生活正好揭示了作为监狱的生活。我在外面的生活是一个监狱,我作为一个自由主体的生活是一个监狱。因为我在说话。因为我是一个说话的主体。而在语言的监狱,作为一个说话的主体,我们却越来越像那些不说话的人,接近动物,被囚禁的动物,以及它们所谓由重复和固定动作构成的刻板行为。

What Hardt describes when he says that prison is everywhere, that our lives are always already captured by power, is the series of stereotypes in which we are always already locked in—those repetitions, habits, routines, and manifestations of meaninglessness that first appear in language, and are redoubled by philosophy.

当哈特说监狱无处不在,我们的生活总是已经被权力所捕获时,他所描述的是我们总是已经被锁在其中的一系列定型观念--那些重复、习惯、例行公事和无意义的表现,它们首先出现在语言中,并被哲学所加倍。

Prison as a Condition for Liberation

监狱作为解放的一个条件

Barthes also characterizes the originary entanglement of power and language as what gives way to the production of stererotypes:

巴特还将权力与语言的原始纠缠描述为生产定型观念的途径:

The sign is a follower, gregarious; in each sign sleeps that monster: a stereotype. I can speak only by picking up what loiters around in speech. Once I speak, these two categories unite in me; I am both master and slave. I am not content to repeat what has been said, to settle comfortably in the servitude of signs: I speak, I affirm, I assert tellingly what I repeat. In speech, then, servility and power are inescapably intermingled.10

符号是一个追随者,好聚好散;在每个符号中都沉睡着那个怪物:一个刻板印象。我只有通过捡起在语言中游荡的东西才能说话。一旦我说话,这两个类别在我身上结合起来;我既是主人又是奴隶。我不满足于重复已经说过的话,不满足于安于符号的奴役。我说话,我肯定,我断言我重复的东西。那么,在说话中,奴性和权力不可避免地交织在一起。

Philosophy usually radicalizes such a situation by affirming that captivity is not a specific state or mode of being among others, but constitutes the very form of being in the world. This means that power would not only be the external force that subdues life and captures it, but also that which exploits a virtuality of life itself, something immanent to life itself. Stereotypic behaviors would then reveal a potentiality of life, something that is always already present in life.

哲学通常将这种情况激进化,肯定囚禁不是一种特定的状态或存在方式,而是构成了世界上存在的形式本身。这意味着权力不仅是制服和捕获生命的外部力量,而且也是利用生命本身的德性的力量,是生命本身所固有的东西。这样一来,刻板的行为就会揭示出生命的一种潜能,一种总是已经存在于生命中的东西。

The specific task of traditional philosophy is to affirm that instead of trying to escape the closure of concepts, we have to first accept it, and to acknowledge the essential complicity between the closure of concepts and the captivity of life. It is the task of philosophy to understand captivity as internal to life. Philosophy, as Plato so powerfully demonstrates with the cave, starts in prison.

传统哲学的具体任务是确认,我们不是要逃避概念的封闭,而是要首先接受它,并承认概念的封闭与生命的囚禁之间的基本共谋关系。哲学的任务是将囚禁理解为生命的内部。正如柏拉图用洞穴有力地证明的那样,哲学始于监狱。

Philosophy wants us to think that there exists something within life that constitutes its own tendency to imprison itself. Heidegger, in his Phenomenological Interpretations of Aristotle (written at a time when he still talked about life and not yet of existence), brings to light the category of Abriegelung—“blocking-off” in English, or verrouillage in French—from Riegel, German for “lock.” Blocking-off is the prefiguration of what he will later express, in Being and Time, as “taking care,” the inauthentic version of care. It is a form of closure, of Benommenheit. Life necessarily imprisons itself, and the lock is an essential structure of life:

哲学希望我们认为,在生命中存在着某种东西,构成了它自己囚禁自己的倾向。海德格尔在他的《亚里士多德现象学解释》中(写于他仍在谈论生命而尚未谈论存在的时候),提出了Abriegelung--英语中的 "封锁",或法语中的verrouillage--来自Riegel,德语中的 "锁"。封锁是他后来在《存在与时间》中表述为 "照顾 "的预兆,是照顾的不真实版本。它是一种封闭的形式,是Benommenheit。生命必然囚禁自己,而锁是生命的一个基本结构。

…life blinds itself, puts out its own eyes. In the sequestration [Abriegelung], life leaves itself out…Factical life leaves itself out precisely in defending itself explicitly and positively against itself.11

......生命蒙蔽自己,熄灭了自己的眼睛。在封存[Abriegelung]中,生命将自己排除在外......真实的生活正是在明确地、积极地反对自己的情况下将自己排除在外。

Why does life need to “[defend] itself…against itself?” The lock, the Riegel coincides with life’s immediate understanding of itself—rather, its misunderstanding of itself as a consequence of the language used to describe that understanding: life appears as something that is ahead of me, as a free space. In stating this, it precisely locks itself out. It misses the authentic opening, which is the opening toward death. Life is imprisoned because it disavows its own death.

为什么生命需要"[保护]自己......反对自己?" 这把锁,Riegel与生命对自身的直接理解相吻合--确切地说,是它对自身的误解,是用来描述这种理解的语言的结果:生命看起来是在我前面的东西,是一个自由空间。在说明这一点时,它恰恰把自己锁在外面。它错过了真正的开放,也就是对死亡的开放。生命被禁锢是因为它不承认自己的死亡。

In the philosophical tradition, the concept of alienation has long been used to designate this originary captivity of life. Michel Henry’s Marx contains an interesting analysis of what he calls “subjective alienation,” as distinct from objective alienation.12 Henry’s thesis is that Marx’s main concern is life, life understood in its most material, empirical determination. In Hegel, Henry explains, alienation characterizes a becoming-object. For example, if I say that my life is alienated, in Hegelese, this means that my life has become a thing. It is true that labor, for Marx, is what transforms life into a commodity, a thing. The problem is that the worker’s life is inseparable from the worker, so what they alienate is something subjective, something that they cannot depart from without dying. Labor is subjective alienation, the selling of something that cannot become an object:

在哲学传统中,异化的概念长期以来一直被用来指称生命的这种起源性俘虏。米歇尔-亨利的《马克思》对他所谓的 "主观异化 "进行了有趣的分析,与客观异化不同。12亨利的论点是,马克思主要关注的是生命,在其最物质的、经验性的决定中理解的生命。亨利解释说,在黑格尔那里,异化的特点是一个成为对象。例如,如果我说我的生命是异化的,在黑格尔那里,这意味着我的生命已经成为一个东西。的确,对马克思来说,劳动是将生命转化为商品、物品的东西。问题是,工人的生命与工人是不可分割的,所以他们异化的是主观的东西,是他们不死也无法离开的东西。劳动是主观的异化,是对不能成为物的东西的出卖。

If alienating oneself does not mean to objectify oneself any longer, to posit oneself in front of oneself as something which is there, alienation then occurs within the very sphere of subjectivity, it is a modality of life and it belongs to it…Alienation is “a specific tonality of life, when life means suffering, sacrifice…” What is the most proper becomes the most alien.13

如果异化自己不再意味着把自己对象化,把自己摆在自己面前作为存在的东西,那么异化就发生在主观性的范围内,它是一种生活方式,它属于它......异化是 "生活的一种特殊调性,当生活意味着痛苦、牺牲......" 最恰当的东西变成了最异化的东西13。

In Henry as well, social alienation comes from an immanent tendency of life. Life is always already alienated, imprisoned, because it cannot speak of its own alienation. It does not have the words. Here again, the first prison is language. The ambiguity of philosophy is that it roots alienation, or Abriegelung, within life itself.

在亨利那里,社会异化也来自于生命的内在倾向。生命总是已经被异化了,被囚禁了,因为它无法说出自己的异化。它没有话语权。在这里,第一个监狱又是语言。哲学的模糊性在于,它将异化或Abriegelung植根于生命本身。

Prison and Disalienation

###监狱与剥夺权利

Philosophers have also thought how to disalienate life, which amounts to elucidating the issue of the outside where there is no outside. Hardt affirms that Genet succeeded in carving out a space of freedom within captivity. He was able to build an outside from inside the prison, an outside which was not an elsewhere:

哲学家们还思考了如何剥夺生命,这相当于在没有外部的地方阐释了外部的问题。哈特肯定,热内成功地在囚禁中开辟了一个自由的空间。他能够从监狱内部建立一个外部,一个不是别处的外部。

The fullness of being in Genet begins with the fact that he never seeks an essence elsewhere—being resides only and immediately in our existence…Exposure to the world is not the search for an essence elsewhere, but the full dwelling in this world, the belief in this world.14

在热内身上,存在的充分性始于这样一个事实,即他从未在其他地方寻求一种本质--存在只立即停留在我们的存在中......接触世界不是在其他地方寻求一种本质,而是完全居住在这个世界上,相信这个世界。

Hardt explains that prison is still a world, and being captive a modality of exposure to the world. And it is from the experience of prison, when we learn how to dwell in prison, that we can get out of it:

哈特解释说,监狱仍然是一个世界,而被囚禁是接触世界的一种方式。而正是从监狱的经验中,当我们学会如何在监狱中居住时,我们才能走出监狱。

When we expose ourselves to the force of things we realize this ontological condition, the immanence of being in existence. We merge with the destiny we are living and are swept along in its powerful flux.15

当我们把自己暴露在事物的力量中时,我们就会意识到这种本体论的条件,即存在于存在中的内在性。我们与我们所处的命运融为一体,并在其强大的流变中被卷走。

The important term here is “immanence,” which means “inside.” There is a possible transcendence in immanence. Through writing, Genet is at one with the bodies of the prisoners, their living bodies: “in this exposure the bodies are fully realized and they shine in all their gestures.”16 This gain in intensity inside is what Hardt calls the saintly, divine, sublime passivity of being in prison. Writing, or as Heidegger would say, thinking—a certain use of language that emancipates the writing or thinking subject from stereotypes.

这里的重要术语是 "immanence",意思是 "内部"。在内在性中存在着一种可能的超越。通过写作,热内与囚犯的身体、他们的生命体融为一体。"在这种暴露中,身体被完全实现了,它们在所有的姿态中闪闪发光。"16这种内部强度的提高就是哈特所说的在监狱中的圣洁的、神圣的、崇高的被动性。写作,或者像海德格尔所说的,思考--某种语言的使用,将写作或思考的主体从定型中解放出来。

Hardt uses a Spinozist, Nietzschean, and Deleuzian vocabulary to characterize how Genet increases his power of acting, how life becomes joy, affirmation, creation, in the “energy of erotic exposure” of captive life. This transcendence in immanence is not only an artistic or erotic gesture; it is a revolutionary one. Hardt even begins his article by writing: “Lenin liked to think of prison as a university for revolutionaries.”17 But “exposure itself, however, is not enough for Genet.”18 Exposure has to transmute itself into the revolutionary event. Instead of getting out, into the outside, the externality comes from a reversion from within. Writing is an enduring movement that inverts directions.

哈特用斯宾诺兹主义、尼采和德勒兹的词汇来描述热内如何增加他的行动力,如何在被囚禁的生命的 "情欲暴露的能量 "中使生命成为快乐、肯定、创造。这种在内在性中的超越不仅是一种艺术或色情的姿态;它是一种革命的姿态。哈特甚至在文章的开头就写道 "列宁喜欢把监狱当作革命者的大学。"17但 "暴露本身对热内来说是不够的。"18暴露必须把自己转化为革命的事件。与其说是走出去,到外面去,不如说是外部性来自内部的还原。写作是一种颠倒方向的持久运动。

Revolution is defined by the continuous movement of a constituent power…Revolutionary time finally marks our escape from prison time into a full mode of living, unforeseeable, exposed, open to desire. This mode of living is at all times constituent of our new, revolutionary time.19

革命是由一种构成力量的持续运动所定义的......革命的时间最终标志着我们从监狱的时间中逃脱出来,进入一种完整的生活模式,不可预见的,暴露的,对欲望开放的。这种生活模式在任何时候都是我们新的、革命的时间的组成部分。

The redemption of prison space first has to happen within prison itself. In the thesis defended by Hardt and Negri in Multitudes, prison time characterizes the situation of the global proletariat, the carceral mode of living imposed upon it by globalization. We find here again the point made by Henry about subjective alienation and the cutting of life in two by the capitalist exploitation of labor. The revolution to come appears first as a revolution of language in language. Barthes again:

监狱空间的救赎首先必须发生在监狱本身。在Hardt和Negri在Multitudes中捍卫的论点中,监狱时间是全球无产阶级状况的特征,是全球化强加给他们的生活模式。我们在这里再次发现了亨利提出的关于主观异化和资本主义对劳动的剥削将生活一分为二的观点。即将到来的革命首先表现为语言中的语言革命。巴特又说:

But for us, who are neither knights of faith nor supermen, the only remaining alternative is, if I may say so, to cheat with speech, to cheat speech. This salutary trickery, this evasion, this grand imposture which allows us to understand speech outside the bounds of power, in the splendor of a permanent revolution of language, I for one call literature.20

但对我们这些既不是信仰骑士也不是超人的人来说,剩下的唯一选择就是,如果我可以这么说的话,用语言作弊,欺骗语言。这种有益的诡计,这种回避,这种使我们能够在权力的界限之外理解语言的大骗局,在语言的永久革命的光辉中,我称之为文学20。

Revolution starts with an upheaval of language, an event that keeps language “alive.” Such an operation coincides with Hardt and Negri’s “liberation of living labor,” the counterpower to “Empire seen as a mere apparatus of capture that lives off the vitality of the multitude.”21

革命始于语言的动荡,一个让语言保持 "活力 "的事件。这样的行动与哈特和奈格里的 "活劳动的解放 "不谋而合,是对 "帝国被视为仅仅是依靠众人的活力而生存的捕获机器 "的反击。

Life, through revolution, does not negate its capacity to be captured, its essential relationship to exile, closure, and separation. The originary passivity of life can always be exploited and subjugated by revolution itself. Therefore, there is no clear and univocal meaning of the way out.

生命,通过革命,并没有否定其被捕获的能力,其与流放、封闭和分离的基本关系。生命的原始被动性总是可以被革命本身所利用和征服。因此,没有明确的、统一的出路的意义。

What does the outside look like? This question is very difficult, and to answer it requires taking a different direction. The outside of prison though revolution consists mostly in the transformation of the social jail into the emancipated community, the building and fashioning of the commune, of networks of interrelationality. Through this network, life returns to itself, is restituted to itself. But this interrelationality, in turn, can be considered a new prison. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. affirms in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail”:

外面是什么样子的?这个问题非常困难,要回答这个问题需要采取不同的方向。监狱的外面虽然是革命,但主要包括将社会监狱转变为解放的社区,建立和塑造公社,建立相互关系的网络。通过这个网络,生命回到了自身,被还原到了自身。但这种相互关系,反过来,也可以被认为是一个新的监狱。正如小马丁-路德-金博士在他的 "伯明翰监狱来信 "中所确认的:

In a real sense all life is interrelated. All men are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be…This is the interrelated structure of reality.22

在一个真正的意义上,所有的生命都是相互关联的。所有的人都被卷入一个不可避免的相互关系的网络中,被绑在一件命运的衣服上。凡是直接影响到一个人的,都会间接影响到所有人。在你成为你应该成为的人之前,我永远不可能成为我应该成为的人,而在我成为我应该成为的人之前,你永远不可能成为你应该成为的人......这就是现实的相互关联结构。

Black Death and the End of Prison Idealism

黑人之死与监狱理想主义的终结

King’s words describe something like the universal condition of life, what all people share, caught as they are in the same net. The “inescapable network” may be considered the origin of freedom, in the same way that Sartre said that men are doomed, or destined to be free.

金的话语描述了一些类似于生命的普遍状况,即所有的人都有的东西,因为他们被抓在同一张网里。这个 "无法逃脱的网络 "可以被认为是自由的起源,就像萨特说人是注定的,或注定要自由一样。

However, they can also be read as announcing a new mode of being locked in, within the community and the revolutionary act itself. The network formed by humanity, even if interrelated, is a mechanism of exclusion.

然而,它们也可以被解读为宣布了一种新的被锁定的模式,在社区和革命行为本身中。人类形成的网络,即使是相互关联的,也是一种排斥的机制。

In his book Red, White & Black, Frank Wilderson proposes an interpretation of Hardt’s text from the point of view of Afro-pessimism.23 For Wilderson, Hardt’s analysis acts like a lock and a new modality of separation. His discourse on revolution “assumes a universal grammar of suffering,” which does not exist. There is no universal grammar of prison or concepts of imprisonment. The very concept of life, Wilderson states, necessarily precludes Blackness: “Black time is the moment of no time at all on the map of no place at all.”24 The duality inside/outside cannot apply to Blackness.

弗兰克-维尔德森在他的《红、白、黑》一书中,从非洲悲观主义的角度提出了对哈特文本的解释。23对维尔德森来说,哈特的分析像一把锁和一种新的分离模式。他关于革命的论述 "假定了一种普遍的苦难语法",而这种语法并不存在。监狱或监禁的概念也没有普遍的语法。怀尔德森说,生命的概念本身必然排除了黑色。"黑人的时间是在没有任何地方的地图上没有时间的时刻。"24内部/外部的二元性不能适用于黑人。

The slave, who for Wilderson is the fundamental identity of Blackness, is not a prisoner, but a slave; that is, a non-being, a life that is not one. “Marxist…[ontologies] either take for granted or insist on…the a priori nature of the subject’s capacity to be alienated and exploited.”25 Revolution itself is a concept, is a capture. “One cannot think loss and redemption through Blackness, as one can think them through the proletarian multitude or the female body, because Blackness recalls nothing prior to the devastation that defines it.”26

对威尔德森来说,奴隶是黑人的基本身份,他不是一个囚犯,而是一个奴隶;也就是说,一个非存在,一个不是一个的生命。"马克思主义的......[本体论]要么想当然,要么坚持......主体被异化和剥削的能力的先验性质。"25革命本身是一个概念,是一种捕捉。"我们不能通过黑人来思考损失和救赎,就像我们可以通过无产阶级众人或女性身体来思考它们一样,因为黑人在定义它的破坏之前,什么都不会想起。" 26。

Furthermore, Wilderson states that “Blackness exists on a lateral plane where it is possible to rank human with animal.”27 The Black subject is therefore exiled from the human relation, which is predicated on social recognition, volition, subjecthood, and the valuation of life itself. For Wilderson, Black existence is marked as an ontological absence posited as sentient object and devoid of any positive relationality, **in contradistinction to the presence of the human subject. White life is constructed upon Black death, whereas Black lives are Black deaths.

此外,怀尔德森指出,"黑人存在于一个横向的平面上,在这个平面上有可能将人与动物相提并论。"27因此,黑人主体被放逐出人的关系,这种关系是以社会承认、意志、主体性和对生命本身的评价为前提的。对Wilderson来说,黑人的存在被标记为一种本体论的不存在,被认为是有生命的物体,没有任何积极的关系性,与人类主体的存在相矛盾。白人的生命是建立在黑人的死亡之上的,而黑人的生命就是黑人的死亡。

Philosophy and literature never take into account lives that are excluded by the concept or the immanent passion of the word. When Wilderson affirms that Blackness is ranked with animal life, it is to the extent that animal life itself is excluded from the concept, and that Black lives and animal lives are both reduced to pure stereotypes.

哲学和文学从未考虑到被概念或词的潜在情绪所排斥的生命。当怀尔德森肯定黑人与动物生命并列时,是在把动物生命排除在生命的概念之外,而黑人生命和动物生命都被简化为纯粹的刻板印象。

Black Lives Matter, the international activist movement created in July 2013, has evoked many reactions. Its perception in the US varies considerably. The phrase “All Lives Matter” sprang up as a response to the Black Lives Matter movement. However, “All Lives Matter” has been criticized for dismissing or misunderstanding the message of “Black Lives Matter.” And following the shooting of two police officers in Ferguson in 2014, the hashtag “Blue Lives Matter” was created by supporters of the police.

黑人命关天 "是2013年7月创立的国际活动家运动,它引起了许多反应。而在美国,对其看法有很大的不同。作为对 "黑人生命重要 "运动的回应,"所有生命都重要 "这一短语应运而生。然而,"所有生命都重要 "被批评为否定或误解了 "黑人生命重要 "的信息。而在2014年弗格森两名警察被枪杀后,警察的支持者们创造了 "蓝色生命重要 "的标签。

We can see through this example that life, whatever its definition, seems to always fall back into ghetto, prison, separation, and fragmentation. Blackness is the most obvious case of the impossibility to open a space of freedom within life, because Black life is deprived of any inside; it is always already emptied by non-Black concepts of non-Black lives.

通过这个例子我们可以看到,生活,无论其定义是什么,似乎总是回到贫民窟、监狱、分离和分裂。黑人是不可能在生活中打开自由空间的最明显的例子,因为黑人的生活被剥夺了任何内在;它总是已经被非黑人的非黑人生活的概念所掏空。

In conclusion, literature and philosophy, as Barthes, Hardt and Genet define them, are others ways of reintroducing a form of almost religious transcendence within the analysis of life as closure and the fascist essence of language. Revolution remains idealized as a way of finding one’s own salvation from within the prison of reality. What kind of language has then to be found that would not be a reimprisonment of Black lives? Does it still belong to philosophy? Does it still belong to literature? For sure, this issue requires the opening of a yet unheard of space. Afro-pessimism might be its name. A name born in prison.

总之,文学和哲学,正如巴特、哈特和热内所定义的那样,是在对作为封闭的生活和语言的法西斯本质的分析中重新引入一种近乎宗教的超越的其他方式。革命仍然被理想化为一种从现实的监狱中找到自己的救赎的方式。那么,要找到什么样的语言才不会是对黑人生命的重新囚禁?它仍然属于哲学吗?它还属于文学吗?可以肯定的是,这个问题需要开辟一个尚未听说过的空间。非洲悲观主义可能是它的名字。一个在监狱中诞生的名字。

Notes

1

Roland Barthes, “Inaugural Lecture at the Collège de France,” in The Continental Philosophy Reader, eds. Richard Kearney and Maria Painwater (New York: Routledge, 1996), 365–366.

2

Ibid., 366.

3

Cf. Frederic Jameson, The Prison-House of Language: A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian Formalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975).

4

See “Captive,” Online Etymology Dictionary, ➝; see also “Prison,” ➝.

5

“Prison,” Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales, 2012, ➝.

6

Michael Hardt, “Prison Time”, in Yale French Studies, “Genet: In the Language of the Enemy,” special issue 91 (1997): 64–79.

7

Ibid., 66.

8

Ibid., 66–67.

9

“Stereotypic behaviour is an abnormal behaviour frequently seen in laboratory primates. It is considered an indication of poor psychological well-being in these animals. It is seen in captive animals but not in wild animals…Stereotypic behaviour has been defined as a repetitive, invariant behaviour pattern with no obvious goal or function. A wide range of animals, from canaries to polar bears to humans can exhibit stereotypes. Many different kinds of stereotyped behaviours have been defined and examined. Examples include crib-biting and wind-sucking in horses, eye-rolling in veal calves, sham-chewing in pigs, and jumping in bank voles. Stereotypes may be oral or involve bizarre postures or prolonged locomotion. A good example of stereotyped behaviour is pacing. This term is used to describe an animal walking in a distinct, unchanging pattern within its cage…The locomotion may be combined with other actions, such as a head toss at the corners of the cage, or the animal rearing onto its hind feet at some point in the circuit.” Nora Philbin, “Towards an understanding of stereotypic behaviour in laboratory macaques,” Animal Technology: Journal of the Institute of Animal Technicians 49, no. 1 (1998): 19–33.

10

Barthes, “Inaugural Lecture,” 368.

11

Martin Heidegger, Phenomenological Interpretations of Aristotle, trans. Richard Rojcewicz (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 80.

12

Michel Henry, Marx: A Philosophy of Human Reality, trans. Kathleen MacLaughlin (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993).

13

My translation. Ibid., 608.

14

Hardt, “Prison Time,” 67–68.

15

Ibid., 68.

16

Ibid.

17

Ibid., 64.

18

Ibid., 70.

19

Ibid., 68.

20

Barthes, “Inaugural Lecture,” 369.

21

Michael Hardt and Tony Negri, Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 61–62.

22

Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Birmingham City Jail, April 16, 1963.

23

Frank B. Wilderson, Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010).

24

Ibid., 279.

25

Ibid.

26

Ibid., 281.

27

Ibid., 288.