《救赎》:消除

作者:Chris Fujiwara

发表时间:2022/10/18

翻译:小饰

原文链接:Cure: Erasure

Films about serial killers often combine the police thriller with the horror film. In his tense and atmospheric Cure (1997), Kiyoshi Kurosawa deepens the implications of this hybrid genre. Discarding the reassurances typically associated with the police in such films, he widens the social, political, psychological, and metaphysical issues surrounding random violent death and, in so doing, brings out the full irony and ambiguity of his deceptively simple title.

关于连环杀手的电影经常将警匪惊悚片与恐怖片结合起来。在他充满紧张氛围的《Cure》(1997年)中,黑泽清深入了这种混合类型片的含义。他摒弃了此类影片中通常与警察有关的印象,扩大了围绕随机暴力死亡的社会、政治、心理和形而上学问题,并这个过程中,充分体现了这个简单标题(Cure)的讽刺和模糊。

Born in 1955, Kurosawa belongs to the generation that came of age in Japan at a time when the collapse of the student political movements of the sixties and early seventies had left young people with the sense that their identities were, in his words, “uncertain and indefinite.” Having been marked by the American cinema of the seventies, and having honed his craft as a director of low-budget and straight-to-video movies beginning in the eighties, Kurosawa was, by the late nineties, well versed in the strategies by which a filmmaker can challenge producers’ and audiences’ expectations while playing at satisfying them. He brought to Cure, the film that won him international attention and set the pattern for his subsequent career, a sense of the contradictions within Japanese society and a confident understanding of how they can be addressed within genre cinema.

黑泽明生于1955年,属于在日本60年代和70年代初的学生政治运动的崩溃中成年的一代人。在那时年轻人感到他们的身份,用他的话说,"迷茫和不确定"。由于受到70年代美国电影的影响,并且从80年代开始使用低成本和直接录像带磨练自己的技艺,黑泽明在90年代末已经深谙一个导演在挑战制片人和观众期望的同时又能满足他们的策略。他为《Cure》这部电影带来了对日本社会内部矛盾的认识,以及对如何在类型电影中处理这些矛盾的自信,这部电影为他赢得了国际关注,并为他随后的职业生涯奠定了基础。

Committed by different people, the killings in Cure are linked only by slashes in the shape of an X across the neck of each corpse. The film hints that long-festering resentments figured in the background of at least two of the crimes. Surfacing among people who seem to be model representatives of their society (a schoolteacher, a police officer, and a doctor among them), this resentment assumes the dimensions of a social problem, albeit one that the film refuses to identify and that the detective in charge of the case, Takabe (Koji Yakusho), declines to explore. Takabe determines that each killer had been hypnotized during an encounter with a former psychology student, Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), whose own motives remain unknown. To the extent that viewers wish to see Mamiya punished, the film diverts the audience from the search for a “cure” and into the desire to see unleashed the vengeful police power that has been a traditional component of serial-killer films since Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry.

由不同的人所为,《Cure》中的杀戮只因每具尸体的脖子上有X形的划痕而有联系。影片暗示,至少有两起案件的背景中存在着长期的怨恨。这些人似乎是社会的模范代表(其中包括一名教师、一名警察和一名医生),尽管影片拒绝确认,负责此案的侦探高部(Koji Yakusho)也拒绝探讨,但这种怨恨存在社会问题中的维导。高部确定,每个凶手都是在与以前的心理学学生间宫(萩原正人)相遇时被催眠的,而间宫自己的动机仍然不明。最终观众希望看到间宫受到惩罚的角度上,影片引导观众从寻找 "治疗方法 "转移到了希望看到复仇的警察力量的释放,这是自唐-西格尔的《肮脏的哈里》以来连环杀手电影的一个传统组成部分。

On the other hand, it is possible to regard Mamiya’s project as utopian, rather than merely negative, and to see Mamiya the way he presumably sees himself: as a savior—though if so, the least that could be said is that he has a peculiar way of saving people. If Cure’s portrayal of Takabe owes something to American police thrillers, Mamiya’s hypnotic powers move the film into the realm of the fantastic. Cure establishes what would later become familiar hallmarks of J-horror, as the cycle of Japanese horror films around the turn of the millennium came to be known: the link between media and the supernatural, here represented by an enigmatic silent film that appears to predict the killings (a cursed videotape plays a comparable, though expanded, role in Hideo Nakata’s 1998 Ring, as does dial-up internet in Kurosawa’s own Pulse, from 2001), and the evocation of a mood of creeping dread—most effectively shown in Cure in the slow-burning set pieces in which Mamiya wields his power of suggestion over his delegate assassins.

另一方面,我们有可能将间宫的计划视为乌托邦式的,而不是消极的,并以间宫可能认为自己的方式来看待他:作为一个救世主--尽管如果是这样的话,至少可以说他有拯救人们的方式十分奇特。如果说《Cure》对高部的描写归功于美国惊悚警匪片,那么间宫的催眠能力则使影片进入了梦幻般的境界。 《Cure》确立了千禧年前后被称为J-Horror的日本恐怖片中的熟悉标志:媒介与超自然现象之间的联系。在这里由一部神秘的无声电影代表,它似乎预示着杀戮(在中田英夫1998年的《环》中,一盘被诅咒的录像带发挥了类似的作用,尽管范围扩大了,在黑泽明自己2001年的《脉动》中也是如此),以及唤起一种蠕动的恐惧情绪--在《Cure》中,最直观地体现在间宫行使催眠时缓慢的火焰燃烧场景。

Lacking memories of his own, and able to vanish from the memories of those he hypnotizes, Mamiya can describe other people’s mental images in detail. Uncanny as his powers are, it’s conceivable that they could have a rational explanation: like Jacques Tourneur, Kurosawa is a filmmaker less interested in depicting a world where demons run amok and supernatural causality has free rein than in traveling along the border between the everyday and the supernatural. Mamiya himself is an eccentric variation on a recognizable social type. Iconographically and behaviorally, he is a rebel against Japanese codes of authority, with his long hair and loose sweater, his aggressive air of relaxation, and his insolent habit of questioning people while ignoring their questions.

由于缺乏自己的记忆,并且能够从他所催眠的人的记忆中消失,间宫能够详细地描述其他人的精神图像。尽管他的能力令人毛骨悚然,但可以想象的是,这些能力有一个合理的解释:像雅克-杜尔一样,黑泽明是一个对描述一个恶魔横行、超自然因果关系自由支配的世界不感兴趣的电影人,反而是对沿着日常和超自然之间的边界旅行更感兴趣。间宫本人是一个社会典型的古怪变体。从形象和行为上看,他的长发和宽松的毛衣,咄咄逼人的放松气氛,以及无视别人问题的无礼的习惯,都体现着他是日本权威准则的反叛者。

Mamiya and Takabe might also be seen as each other’s relays in a single movement. In the oddly funny scene in which Takabe presents Mamiya at police headquarters, the two appear side by side as if they were accomplices, and Mamiya even commiserates with Takabe about the obnoxiousness of his superior. Yakusho’s ability to suggest the quiet suffering of a middle-aged salaryman (in the first of a series of scintillating portraits of masculinity in crisis that the actor has created for Kurosawa) makes him an ideal counterpart to Hagiwara’s youthful, arrogant, insinuating evil genius. Takabe is in danger of becoming susceptible to Mamiya’s influence through the strain caused by the worsening mental illness of his wife, Fumie (Anna Nakagawa), as revealed in the deftly staged and acted scenes between the couple—the most touching parts of Cure, showing the ruins of what was evidently once a caring and affectionate partnership.

间宫和高部也可能被看作是彼此在一个动作中的接力者。在高部在警察总部向间宫介绍的那场奇怪的有趣的戏中,两人并肩出现,仿佛他们是同谋,间宫甚至对高部的上司的厌恶感表示同情。役所有能力暗示一个中年工薪阶层的平静的痛苦(在他为黑泽明创造的一系列危机中的男性形象中的第一个),使他成为间宫年轻、傲慢、含蓄的邪恶天才的理想对手。高部因其妻子(中川杏奈)不断恶化的精神疾病而面临易受间宫影响的危险,这一点在这对夫妇之间巧妙上演的场景中得到了揭示--《Cure》中最感人的部分,是表现了曾经是一段充满关爱和亲情的关系的毁灭。

In the pivotal scene in which Takabe visits Mamiya’s hospital cell, the latter says, “Tell me whatever you like. That’s why you came, isn’t it?” Assuming the role of a doctor, Mamiya addresses Takabe as a patient, indicating that a cure is desired, sought, and available. Kurosawa refuses, however, to give this view of the situation the support of his mise-en-scène. In the dimly lit cell, both men’s already questionable identities seem only to become murkier. Finally, the screen is engulfed in abstract patterns of rainwater dripping from the soaked ceiling onto a table and the floor. The moving, splashing water writes an incomprehensible message of destiny. During this scene, Takabe gives voice to an anguished complaint, sounding a note of resentment against all the sick people who, he says, cause all the trouble in the world and turn the lives of normal people like him into hell. Takabe’s bitterness is that of someone who can’t understand why he hasn’t been congratulated for having annihilated his own individuality.

在高部访问间宫医院牢房的关键场景中,后者说:"你想说什么就说什么。这就是你来的原因,不是吗?" 间宫扮演着医生的角色,以病人的身份对高部讲话,表示希望得到治疗,寻求治疗,并且可以得到治疗。然而,黑泽明拒绝给这种情况的观点以他的场景支持。在昏暗的牢房里,两个人本来就可疑的身份似乎变得更加模糊。最后,屏幕被抽象的雨水图案所吞没,这些雨水从浸湿的天花板上滴落到桌子和地板上。移动的、飞溅的水书写着一个难以理解的命运信息。在这个场景中,高部发出了痛苦的抱怨,对所有的病人发出了怨恨的声音,他说,这些人造成了世界上所有的麻烦,把像他一样的正常人的生活变成了地狱。高部的苦闷在于间宫没有

At the end of the film, alone at his table in a restaurant, Takabe appears to have gotten his reward. Contented, in his element, he makes small, perfect moves. He even finishes his dinner (on an earlier visit to the same restaurant, he left his plate almost untouched). The emptiness that was inside him no longer torments him; it has moved outside. In one of those masterstrokes with which a great director suddenly turns a cinematic world inside out, Kurosawa cuts to a close-up of Takabe in profile, from the opposite side of the table. A rack focus shifts our attention to the incongruities contained within the listless space of the restaurant: a teenage girl laughing with her friends at a table, the supervisor putting her hand on the shoulder of Takabe’s server as if she owned her—the main categories of social activity, leisure and work, laid out and exposed, with no principle of coherence to bind them.

在影片的最后,高部独自坐在餐厅的桌子旁,似乎已经得到了他的回报。他很满足,在他的元素中,他做了一些小的、完美的动作。他甚至吃完了他的晚餐(在早些时候访问同一家餐厅时,他几乎没有动过他的盘子)。他内心的空虚不再折磨他;它已经转移到外面。在那些伟大的导演突然将一个电影世界翻转过来的大手笔中,黑泽明切入了高部的侧面特写,从桌子的另一边。一个架子上的焦点将我们的注意力转移到餐厅无精打采的空间里所包含的不和谐因素上:一个十几岁的女孩和她的朋友们在桌子上笑,主管将她的手放在服务员的肩膀上,好像她拥有她--社会活动的主要类别,休闲和工作,被铺开并暴露出来,没有连贯的原则来约束它们。

The film has already hinted at the hollowness of social cohesion. Just as he goes twice to the restaurant, Takabe makes two visits to a dry-cleaning establishment. This small, windowed box is a microcosm of the Japan of Cure. On his first visit, Takabe finds himself standing next to another customer, dressed like a typical salaryman, who—while the clerk has gone into the back of the shop for his order, and oblivious of Takabe’s presence—mutters to himself in a rage, taking imaginary private vengeance for some slight endured at work. As soon as the clerk returns, the man resumes the innocuous persona of an ordinary customer. Takabe, in turn, having remained frozen throughout the man’s tirade, now turns to look at him with an expression that betrays no interest. On his second visit, another disruption: Takabe has lost his ticket, and the clerk, unable to find his garment, offers vaguely condescending suggestions (maybe he took it to a different shop; maybe he gave it to his wife). All it takes is the occurrence of an exception (the lost ticket) for communication to reach an unbridgeable impasse.

影片已经暗示了社会凝聚力的空洞性。就像他去了两次餐馆一样,高部也去了两次干洗店。这个小小的、有窗户的盒子空间是《Cure》中日本的一个缩影。 在干洗店的第一场,高部站在另一个顾客旁边,他的穿着打扮就像一个典型的工薪族,当店员走入店后面时,他对高部的存在视而不见,愤怒地自言自语,为工作中受到的一些轻视进行想象的私人报复。店员一回来,这个人就恢复了普通顾客的无害身份。而高部,在这名男子的咆哮中一直保持沉默,转过头来看着他,表情毫无兴趣。在第二场中,又发生了一次混乱。高部丢失了他的小票,店员找不到他的衣服,提出了一些含糊不清的建议(也许他把它带到了另一家商店;也许他把它给了他的妻子)。只需发生一个例外(丢了票),沟通就会陷入无法弥合的僵局。

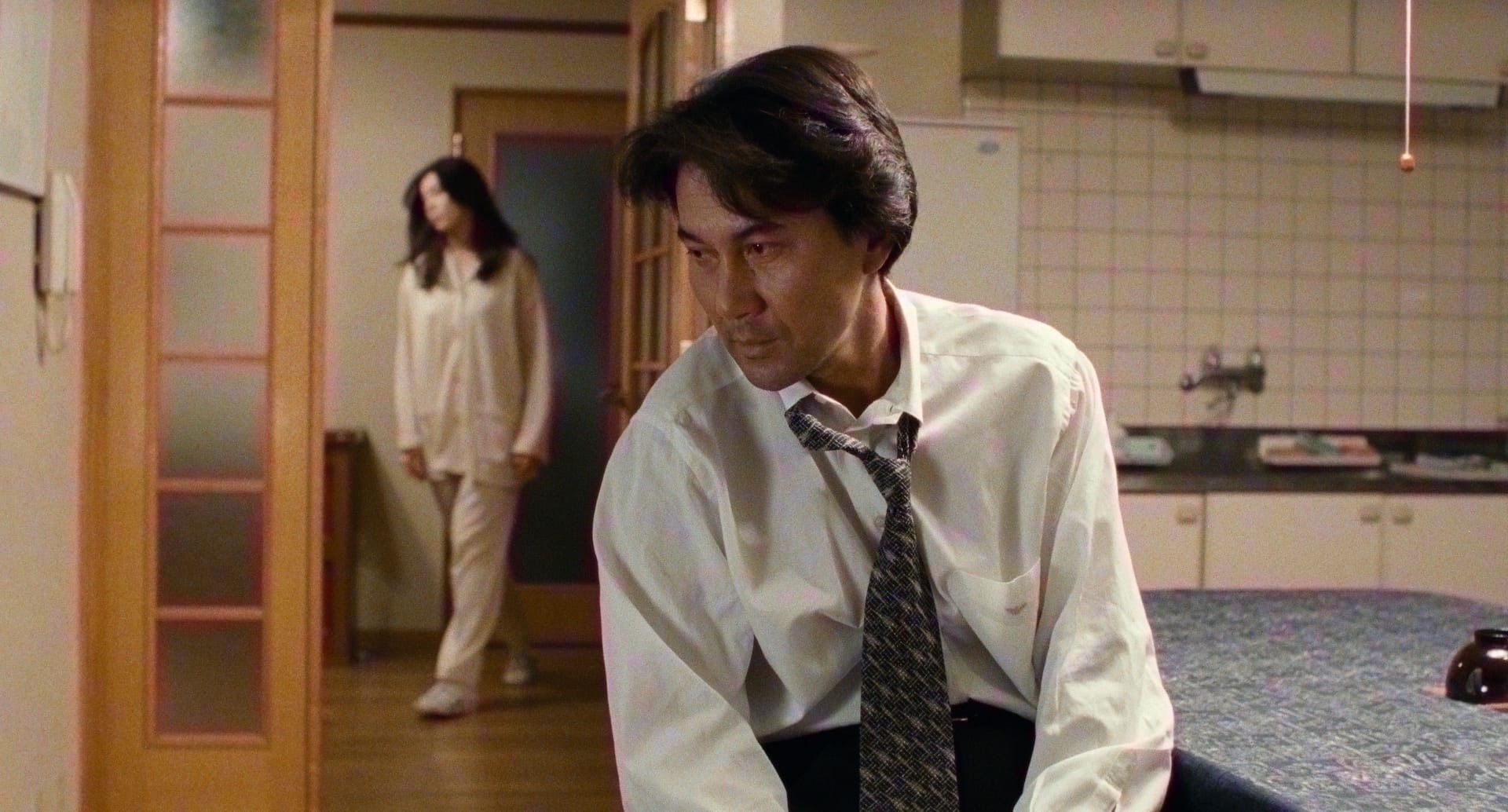

Mamiya carries the possibility of this communal breakdown within him and exposes it in others. He exploits what Hannah Arendt, in her analysis of the emergence of fascism in Germany after World War I, called the “negative solidarity . . . [of a] mass of generally dissatisfied and desperate men.” Not explicitly a political film, Cure analyzes its apolitical landscape with precision. Kurosawa’s significant choice to open the film in Fumie’s psychiatrist’s office predisposes the viewer to see the world of Cure as a limitless psychiatric clinic. Locked within separate cells, the characters concern themselves with private obsessions. Even when they share the same space, they often remain isolated: in a magnificent shot in the Takabes’ apartment, Fumie hurries across the out-of-focus background to switch on the clothes dryer and return to her room, ignoring her husband’s presence in the foreground, where, slumped to one side in his chair, he registers awareness of her movement without turning to face her.

间宫在他身上携带了这种社区崩溃的可能性,并在其他人身上暴露了这种可能性。他利用了汉娜-阿伦特在分析第一次世界大战后德国法西斯主义的出现时所说的 "消极的团结......。[一群普遍不满和绝望的人"。《治愈》并不是明确的政治电影,但却精确地分析了其非政治性的景观。黑泽明选择在文江心理医生的办公室开始影片,这一重大选择使观众倾向于将《治愈》的世界看作是一个无限的精神病诊所。被锁在独立的牢房里,人物关注自己的私人执着。即使他们共享同一个空间,他们也经常保持隔离:在高部夫妇公寓的一个精彩的镜头中,文江匆匆穿过失焦的背景,打开干衣机,回到她的房间,忽略了她丈夫在前景中的存在,在那里,他斜靠在椅子上,意识到她的动作,却没有转身面对她。

These spaces deny an exterior world. Any mental image we could reconstruct of Tokyo from the fragmented narrative might resemble the collection of Polaroids that Takabe lays out on a table before Mamiya. The cell to which Mamiya is transferred is impossibly vast, with its communal-sized lavatory opening from a sprawling main room (in a city as crowded as Tokyo, why would the police hold a suspect in such a big cell?). “I don’t know where ‘here’ is,” says Mamiya to Takabe. In the series of images that make up any film, “here” has no fixed referent but changes from cut to cut; “I don’t know where ‘here’ is” could be said by any film viewer who becomes estranged from the narrative logic that commands a given chain of images. The chains of Cure are, furthermore, subject to slippage. In a scene that may take place inside Takabe’s imagination, he and his wife sit aboard a bus that is apparently not moving, nor is it located in geographic space, except negatively (“We’re not going to Okinawa,” Takabe tells Fumie): its windows offer a view of thick clouds being swept past by the wind.

这些空间否认了一个外部世界。我们可以从零散的叙述中重建东京的精神形象,可能类似于高部在间宫面前的桌子上摆放的宝丽来照片集。间宫被转移到的牢房不可能有多大,它有一个公共大小的盥洗室,从一个宽阔的主房间打开(在东京这样一个拥挤的城市,警察为什么要把一个嫌疑人关在这么大的牢房里?) "我不知道'这里'在哪里,"间宫对高部说。在构成任何电影的一系列图像中,"这里 "没有固定的参照物,而是从一个剪辑到另一个剪辑的变化;"我不知道'这里'在哪里 "可以由任何电影观众说出来,他们变得疏离于指挥某一特定图像链的叙事逻辑。此外,"治愈 "的链条也是可以滑动的。在一个可能发生在高部想象中的场景中,他和他的妻子坐在一辆巴士上,除了消极地("我们不是去冲绳",高部告诉文江),它显然没有移动,也没有位于地理空间中:它的窗户提供了厚厚的云层被风扫过的景色。

The silent film that the police psychologist Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki) shows Takabe is a no less radical narrative disruption. In that film, a Meiji-era hypnotist moves as a dark, faceless blur across the foreground, making an X sign in the air with his hand, the gesture operating, in some ambiguous ritual, both on the female subject seated before the camera and on the viewer. A complex symbol, the X is echoed in Cure by a theme of facelessness: the hypnotized Dr. Miyajima (Yoriko Doguchi) surgically removes the face of her victim on the floor of a public men’s room; Sakuma opens a book that contains the faceless image of a certain Tojiro Hakuraku (the hypnotist of the silent film, one supposes), said to have died in 1898; in the mysterious wooden building where he tracks down Mamiya, Takabe finds a faceless photographic portrait hanging behind a translucent plastic curtain. Carved into the body of each murder victim as a sign of individual erasure, the X also indicates a foreclosure of potential collective action (in a sense, repeating the proscription against hypnotism by the Meiji government, about which Sakuma informs Takabe). It gradually becomes clear that, despite the insignia of nonconformity he brandishes, Mamiya functions as an undercover agent not of utopian rebellion but of repression, spreading fear and widening social fissures.

警方心理学家佐久间(Tsuyoshi Ujiki)给高部看的无声电影是一个同样激进的叙述中断。在那部电影中,一个明治时代的催眠师作为一个黑暗的、无脸的模糊体穿过前景,用他的手在空中做了一个X符号,这个手势以某种模糊的仪式对坐在镜头前的女性对象和观众进行操作。作为一个复杂的符号,"X "在《Cure》中与一个无脸的主题相呼应:被催眠的宫岛医生(Yoriko Doguchi)在公共男厕所的地板上用手术割掉了她受害者的脸;佐久间打开一本书,里面有某位白乐东二郎(据说是默片中的催眠师)的无脸图像,据说他死于1898年;在他追踪麻宫的神秘木楼里,高部发现一幅无脸的摄影画像挂在半透明的塑料帘子后面。在每个被害人的身体上都刻上了X,作为个人被抹去的标志,X也表示对潜在的集体行动的剥夺(佐久间告诉高部,在某种意义上,这重复了明治政府对催眠术的禁止)。渐渐地,我们可以清楚地看到,尽管间宫打着不服输的旗号,但他所扮演的卧底角色不是乌托邦式的反叛,而是镇压,散布恐惧,并进一步扩大社会裂痕。

Near the end of Cure, Kurosawa’s tendency to skip over logical connections and transitional movements becomes more pronounced, reaching a paroxysm with the flash inserts of memory images (linking Fumie to Mamiya in Takabe’s mind) that derail the narrative onto the track of subjective experience. The scene of Takabe and Fumie’s peaceful and mysterious bus ride takes the place of all the missing transitional shots in the film. Like nearly every other element in Cure, the bus transition is doubled: later, on the way to his final confrontation with Mamiya, Takabe is shown riding the same bus alone through the same cloudy sky. These trips show Takabe’s increasing isolation: first, his removal from the sphere of his professional function; then, his separation from his wife (at the end of the film, he may even have killed her, though this is left unclear). Having become a matter of great ambivalence through its dispersal among various characters, the notion of the “cure” now becomes radicalized. If the social problem of the serial killings remains unaddressed in the narrative, it is solved on the formal level, as the erasure of society from the film.

在《Cure》接近尾声时,黑泽明跳过逻辑联系和过渡动作的倾向变得更加明显,随着记忆影像的闪电式插入(在高部的脑海中把妻子和间宫联系起来),使叙事脱离了主观经验的轨道,达到了高潮。高部和妻子平静而神秘的乘车场景取代了影片中所有缺失的过渡性镜头。就像《Cure》中几乎所有的其他元素一样,公交车上的过渡镜头是双倍的:后来,在他与间宫最后对峙的路上,高部被显示为独自乘坐同一辆公交车,穿过同样的阴天。这些旅行显示了高部的日益孤立:首先,他离开了他的专业职能领域;然后,他与妻子分离(在影片的最后,他甚至可能已经杀死了她,尽管这一点并不清楚)。由于分散在不同的角色中,"治愈 "的概念已经成为一个非常矛盾的问题,并且变得激进。如果连环杀人的社会问题在叙事中仍未得到解决,那么它就会在正式层面上得到解决,就像从电影中抹去社会一样。